Rejection of climate protection is a widespread position in right-wing populism. This rejection is often justified by a narrative of a decent people and a corrupt elite. What are the connections behind this argument and nationalistic thinking? By Bernd Sommer and Miriam Schad from Ecological Economy Special Issue O1 – 2023.

“The criticism of the so-called climate protection policy is the third major issue for the AfD after the euro and immigration” (Gauland according to Reusswig et al. 2020, 145). This was announced by Alexander Gauland, the former leader of the Alternative for Germany (AfD), in 2019. Despite some exceptions, the rejection of climate protection has become quite typical of organized right-wing populism. Former US President Donald Trump also linked xenophobia with a withdrawal of environmental and climate protection.

Fossil fascism?

Daggett (2018) used the term “fossil fascism” to describe this connection. This one is in the study White skin, black fuel. On the Danger of Fossil Fascism by Malm and the Zetkin Collective (2021, see article by Söding and Callison in Ecological Economics Vol. 38 No. O1 (2023)); against the background that until recently, climate change received little attention in research on right-wing populism.

Conversely, it is noteworthy that environmental and sustainability research also ignored the topic of rising right-wing populism for a long time. This was the starting point of the research project Policies of Non-Sustainability (PONN), from which some of the central findings are presented below (Sommer et al. 2022). [1]

Right-wing populism and climate protection: positions and explanations

For the study, the literature on climate-relevant positions on right-wing populist blogs as well as from organizations and parties was evaluated. For Germany, according to the study, these were primarily AfD announcements. The questioning of the scientific consensus on anthropogenic climate change is observed, which is sometimes mixed with conspiracy stories.

When it comes to climate change skepticism, the forms of denial differ. The AfD now mostly no longer denies the warming trend itself, but above all the human contribution to it and the need to take climate protection measures.

A dominant narrative in right-wing populism is that climate protection and the energy transition pose a threat to the economy and jobs. In this context, subsidies for renewable energies and the distributional effects of climate protection measures are also criticized.

In terms of content, what should be distinguished from this narrative is that climate protection is a project of the elite that lacks democratic legitimacy. This is also related to a rejection of the EU, which is pushing forward climate protection and the restructuring of the energy sector.

However, the arguments are also mixed with a general skepticism towards the EU, which is seen as a threat to national sovereignty, as well as the fundamental rejection of state intervention in the market or individual freedom.

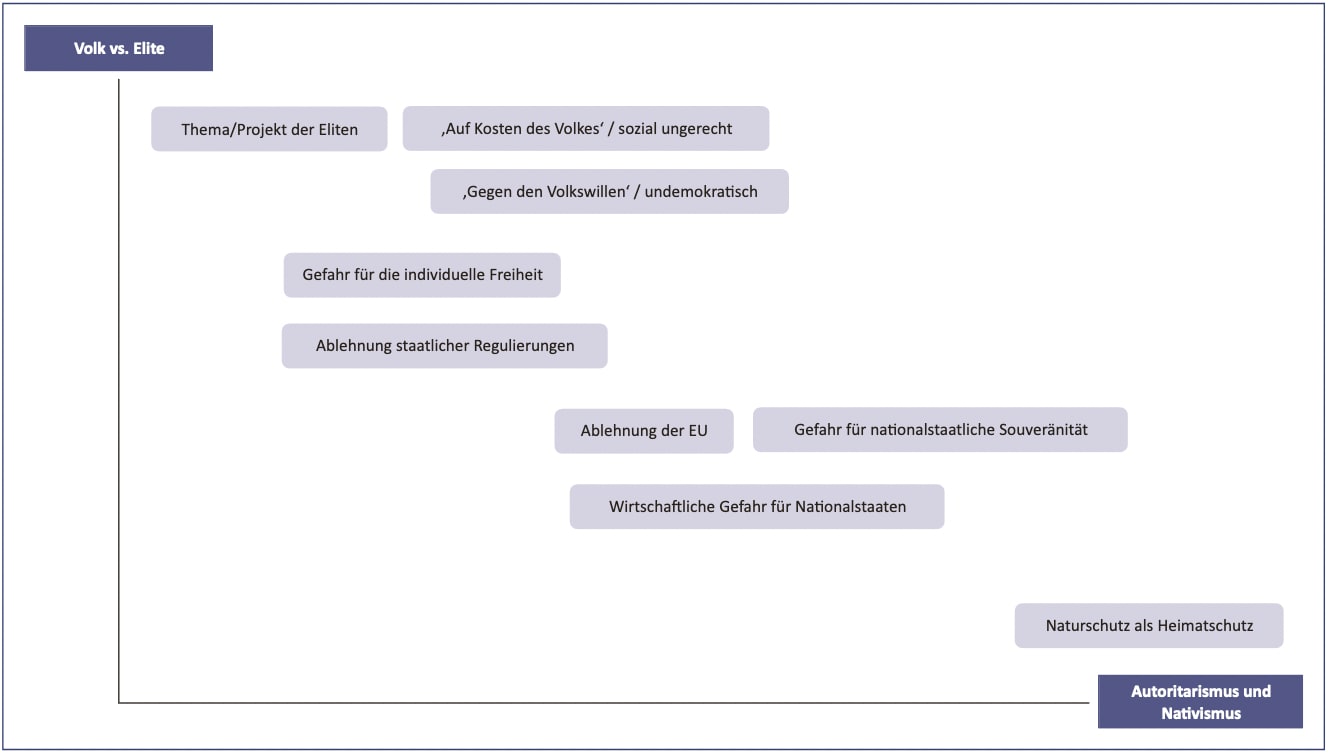

Figure 1: Pattern of justification for the rejection of climate protection in right-wing populism

According to Mudde and Kaltwasser (2019), the populist narrative is characterized by the fact that society is divided into two antagonistic camps: the “decent people” and the “corrupt elite” who act against “the will of the people”. If this “thin ideology” is linked to nationalism and authoritarianism, the literature speaks of right-wing populism. In the reported positions on climate protection, both nationalist and populist core narratives can be identified (see Figure 1).

With regard to the question of how the specific right-wing populist attitudes towards issues of climate and environmental protection can be explained, we were able to identify five different explanations:

A central strand of explanation sees economic reasons as central and argues, for example, that right-wing populist forces create an offer for the losers of the transformation. This can be observed, for example, in Lusatia, where the AfD is committed to continuing the mining of brown coal. Hochschild (2018) argues similarly, describing a “deep story” that is more about perceived disadvantage and the idea that environmental protection regulations prevent people from taking what is considered a legitimate place in society.

According to a second prominent strand of explanation, the aversive attitude of many right-wing populists to climate concerns arises from a fundamental rejection of cosmopolitan values (Lockwood 2018).

Thirdly, a number of authors point out that attitudes that can be characterized as right-wing populist have long and continuously been observed at the attitude level. Parties like the AfD “only” succeed in leveraging this potential.

Fourthly, some of the literature on change in the political field argues that the rejection of climate protection policy is done for strategic reasons in order to appeal to clients such as drivers.

Finally, there are synthetic approaches that take into account economic and cultural factors and their mutual dependency. One example is Eversberg (2018), who interprets the rising right-wing populism as a brutal form of defense of material and cultural privileges that manifested themselves in the dominant imperial way of life.

Outlook: A dynamic field

The research landscape has developed dynamically in the past two years. There are a number of new publications that deal with right-wing populist actors in different countries as well as different forms of populism. Left-wing populist narratives for climate protection are examined (Kemmerzell et al. 2021) or research is carried out on distinctive positions towards ecological sustainability in right-wing political thought (Selk/Kemmerzell 2022).

A content analysis of the members' magazine AfD Kompakt from 2016 to 2020 shows, for example, that criticism of climate protection policy is primarily based on economic and neoliberal positions and, in the sense of a nationalist narrative, is seen as a threat to the national economy.

What is noteworthy here is that features of populism such as criticism of the elite are less frequently observed in the AfD compared to other right-wing populist parties (Küppers 2022).

The disputes over Lützerath or the protests Last generation indicate an intensification of social conflicts in connection with climate protection. Against this background, it can be assumed that its politicization by right-wing populists will continue.

note

[1] The project Politics of Non-Sustainability (PONN): National-authoritarian populism and new social disparities as social framework conditions for a social-ecological transformation was located at the European University of Flensburg and the TU Dortmund from June 1, 2020 to July 31, 2021 and was financed by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) (funding code: 01UV2071 A+B). Detailed information about the project is available here: www.uni-flensburg.de/nec/forschung/ponn

literature

Daggett, C. (2018): Petro-masculinity – Fossil Fuels and Authoritarian Desire. In: Millennium: Journal of International Studies 47/1: 25–44. DOI: 10.1177/0305829818775817

Eversberg, D. (2018): Inner-imperial struggles – three theses on the relationship between authoritarian nationalism and the imperial way of life. In: PROCLA. Journal for Critical Social Science 48/190: 43–54. DOI: 10.32387/prokla.v48i190.31

Hochschild, AR (2018): Strangers in their own country – Anger and mourning on the American right. New York, The New Press.

Kemmerzell, J./Selk, V./Sonnicksen, J. (2021): Populism for the climate? Opportunities and limits of left-wing populist climate policy. In: Kim, S./Selk, V. (eds.): What next with populism research? Baden-Baden, Nomos. 137-158. DOI: 10.5771/9783748922773-135

Küppers, A. (2022): 'Climate-Soviets,' 'Alarmism,' and 'Eco-Dictatorship' – The Framing of Climate Change Scepticism by the Populist Radical Right Alternative for Germany. In: German Politics: 1–21. DOI: 10.1080/09644008.2022.2056596

Lockwood, L. (2018): Right-wing populism and the climate change agenda – exploring the linkages. In: Environmental Politics 27/4: 712–732. DOI: 10.1080/09644016.2018.1458411

Malm, A./Zetkin Collective (2021): White Skin, Black Fuel – On the Danger of Fossil Fascism. London, verso

Mudde, C./Kaltwasser, CR (2019): Populism – A very short introduction. Bonn, Federal Agency for Civic Education.

Reusswig, F./Lass, W./Bock, S. (2020): Farewell to NIMBY – transformations of the energy transition protest and populist discourse. In: Research journal social movements 33/1: 140–160. DOI: 10.1515/ fjsb-2020-0012

Selk, V./Kemmerzell, J. (2022): Positions on sustainability in right-wing political thought – fundamental politicization, neutralization and retrograde adaptation. In: Journal of Politics 69/3: 303–318. DOI: 10.5771/0044-3360-2022-3-303

Sommer, B. et al. (2022): Right-wing populism vs. climate protection? Positions, attitudes, explanations. Munich, oekom.