If the work of human rights defenders is prevented, the people who suffer most are those who urgently need their support: people on the run. They are denied basic rights. An article from “Atlas of Civil Society 2023: Dangerous Assistance”.

260 kilometers, it is no further from Zarzis in the south of Tunisia to Lampedusa. But the 18 people who boarded a boat here on September 21, 2022 to get to Italy never arrived. Their ship sank and they all drowned. None were older than 25; the youngest victim was a 14-month-old baby.

As early as September 23rd, relatives had asked the coast guards of Tunisia, Italy and Malta for help. But the coast guards did nothing to find the missing boat. The Sea Watch 3 of the German NGO of the same name could have started the search.

But on that very September 23rd, the Italian authorities detained the rescue ship in Reggio Calabria in southern Italy because it had previously brought 427 people ashore. Too many, the authorities argued: This number of rescued people was “a danger to people, property or the environment,” according to the inspection report.

The Sea Watch 3 was not allowed to sail again for months. The European Court of Justice only decided in August 2022 that authorities may only inspect ships belonging to humanitarian organizations if they “concretely and in detail demonstrate that there is reliable evidence of a danger.”

From that day to the end of the year, the UN migration agency IOM recorded 276 deaths in the central Mediterranean. That's two human lives per day.

Perfidious agent laws

Private NGOs have sent around 40 ships to the Mediterranean for sea rescue since 2014 – a mobilization effort by civil society. Without them, far more than the 26,000 people who have drowned since then would probably have drowned.

But attempts by the authorities to block the “civilian fleet” are as old as they are: after rescue operations, they are often denied entry into a port for weeks. They are arrested on flimsy grounds – mostly because of alleged technical defects – like the Sea Watch 3. Ships are confiscated, crews taken into custody or subject to legal proceedings.

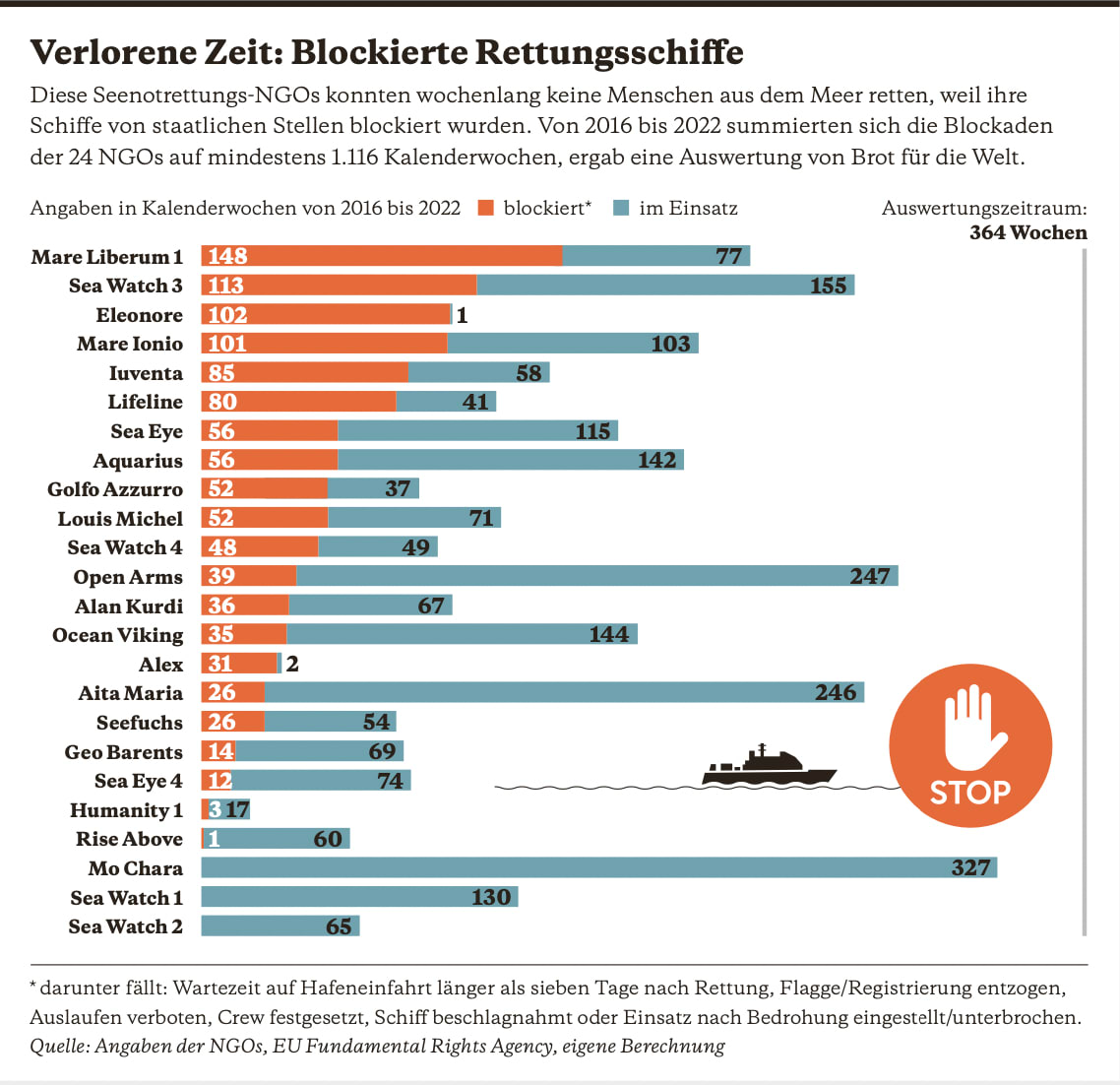

According to research by Bread for the World, the rescue ships sent by NGOs to the Mediterranean since 2016 were blocked for 1,116 weeks – 32 percent of the possible operational weeks at sea (see graphic). The rest of the time they were blocked. The blockade of sea rescue is today one of the most publicly visible strategies to make civil society engagement more difficult in order to curb migration itself.

The calculation: If less is saved, fewer refugees will arrive at some point. However, there is no evidence for this deeply immoral attitude.

The NGO Borderline Europe has been documenting the attacks for years. “Individuals and organizations that advocate for the rights and dignity of people on the run are systematically defamed, harassed and persecuted by state authorities,” writes Borderline. The sociologists Elias Steinhilper and Donatella della Porta find that when it comes to migration, “shrinking space is most visible to civil society.” In the course of criminalizing support for refugees and migrants, many states have expanded the definition of terrorism, enacted new laws against alleged incitement and new secrecy regulations, or even made it more difficult for organizations to collect donations.

The “agent laws” have proven to be a perfidious instrument, the number of which has grown enormously worldwide in the last 20 years. NGOs – especially those that receive money from partners abroad – are suspected of espionage under these laws. In this way, critical voices are controlled and control and information activities of civil society organizations are eliminated.

The UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders, Mary Lawlor, also sees the allegations of alleged money laundering or counterterrorism as a pretext for the restrictions on foreign financing of NGOs. “The real intention of the governments is to restrict human rights organizations in their legitimate work.”

Read more: Climate flight – How the climate crisis is triggering global migration movements

This policy is as international as global migration itself. In Myanmar, for example, in 2021 extremists shot Mohammed Mohib Ullah, a human rights defender who had campaigned for Muslim Rohingya refugees. In June 2022, police in Turkey arrested around two dozen employees of the Migration Monitoring Association for alleged “membership in an armed organization.” In Thailand, a court sentenced Andy Hall, an employee of the Migrant Worker Rights Network, to an initial four years in prison. A state-owned agricultural company had reported him because he had written an article about its treatment of migrants. The proceedings, which resulted in an acquittal, dragged on from 2013 to 2020. And in the Philippines, Migrante International, an organization that supports Filipino migrant workers, fell victim to so-called “red-tagging”: they were defamed as an alleged communist or terrorist organization. What all cases have in common is that security and other laws were abused.

Spongy formulations

In order to silence critical voices, they are often accused of disinformation. When the NGO Human Rights Watch (HRW) wanted to publish a report on the deportation of hundreds of thousands of Afghans from Turkey on November 18, 2022, HRW employee Bill Frelick received a text message from the head of the Turkish presidential office the night before Immigration. HRW demanded that publication be postponed to give Turkey more time to comment. HRW had asked for a statement weeks before.

If Frelick had agreed to the postponement, his report would have appeared just after Turkey's new disinformation law came into force. Its Article 29 is directed against false information that is likely to disrupt the “internal peace of Turkey” – a vague formulation that is open to wide interpretation. And anyone who violates the new rule can now be imprisoned for three years.